The Moon was Full on February 1st, and will be New on the 17th. That day there’s an annular eclipse of the Sun at the coast of Antarctica, partial for the rest of Antarctica, south-east Africa and the southern Indian Ocean.

The Moon is between Venus and Mercury on the 18th, near Saturn on the 19th and Mercury on the 20th, passing Jupiter on the 26th and 27th, and the ‘Beehive Cluster’ Praesepe in Cancer on the 28th.

Interesting results continue to come from the Chinese lunar Farside sample return by Chang’e-6 in 2024. The most recent one is the discovery of carbon nanotube material, which hitherto has only been known as an industrial product on Earth. Apparently it was formed by an impact on carbonaceous material, and before getting excited about a possible artificial origin, it’s important to review the background. Large molecules of carbon-60 were once a purely theoretical possibility, though there was evidence for them in interstellar clouds and eventually they were duplicated in the laboratory by beaming carbon atoms at extremely cold targets in vacuum. The targets were extremely small, and at one of the IBM Heathrow Conferences which I attended, one of the discoverers said that the material’s cost per square foot was huge, making the office carpet seem like less of an extravagance. It seemed doubly ironic when not long afterwards, carbon-60 was discovered to be a common constituent of chimney soot.

The ‘standard’ carbon-60 molecule proved to consist of 60 carbon atoms in a roughly spherical form made up to 6-atom platelets, leading to them swiftly being nicknamed ‘Buckyballs’ or ‘Buckminsterfullerene’, after the geodesic structures pioneered by the architect Buckminster Fuller. One feature that they had in common was that to stabilise a spherical or hemispherical structure, one of the platelets had to be a pentagon and not a hexagon. The resulting shape was instantly recognisable to World Cup fans and the same lecturer added that while Einstein had dismissed quantum theory on the grounds that ‘God does not play dice with the Universe’, it did now appear that He does play football.

How true that would be depends on how common Buckyballs are, and indeed it wasn’t long before their existence was confirmed both in the gases surrounding the eruptive star R Coronae Borealis (Fig. 1) and in interstellar dust in the Small Magellanic Cloud (Fig. 2). What caused still more of a stir was that they could combine into threadlike ‘nanotubes’, with sufficient structural strength to allow the construction of a ‘space elevator’ from geosynchronous orbit to the Earth’s surface (Figs. 3 & 4) – swiftly leading to fictional versions in Arthur C. Clarke’s novel The Fountains of Paradise (Fig. 5) and the late Charles Sheffield’s Web of Everywhere.

Space elevators could be built down from the lunar L1 and L2 points to the surface, but ironically, in lunar gravity these could be built with existing materials such as Kevlar, where the Earth elevator would need ‘super-strength’ ones such as carbon nanotubes. (Jerome Pearson, ‘Anchored Lunar Halo Satellites for Cislunar Transportation and Communication’, L5 Society Western Europe Conference, London, 1977.) Already I’ve seen hints online that the discovery of nanotubes on the Farside of the Moon indicates the presence of a previously high-technology civilisation there, if not a current one. Much more probably, it could have been formed by impact on carbonaceous material, possibly deposited by carbonaceous asteroid, or a comet, or formed on one of those in the first place and already existing before it was deposited on the Moon. If nanotubes prove to be common in space, explanations like that become still more likely, even if carbonaceous material is rare on the Moon itself. It was virtually non existent in the Apollo samples from the Moon’s Nearside. But before it starts again, these new results from Chang’-6 give no excuse for the mantra, ‘Why is NASA lying to us?’, which will probably come next.

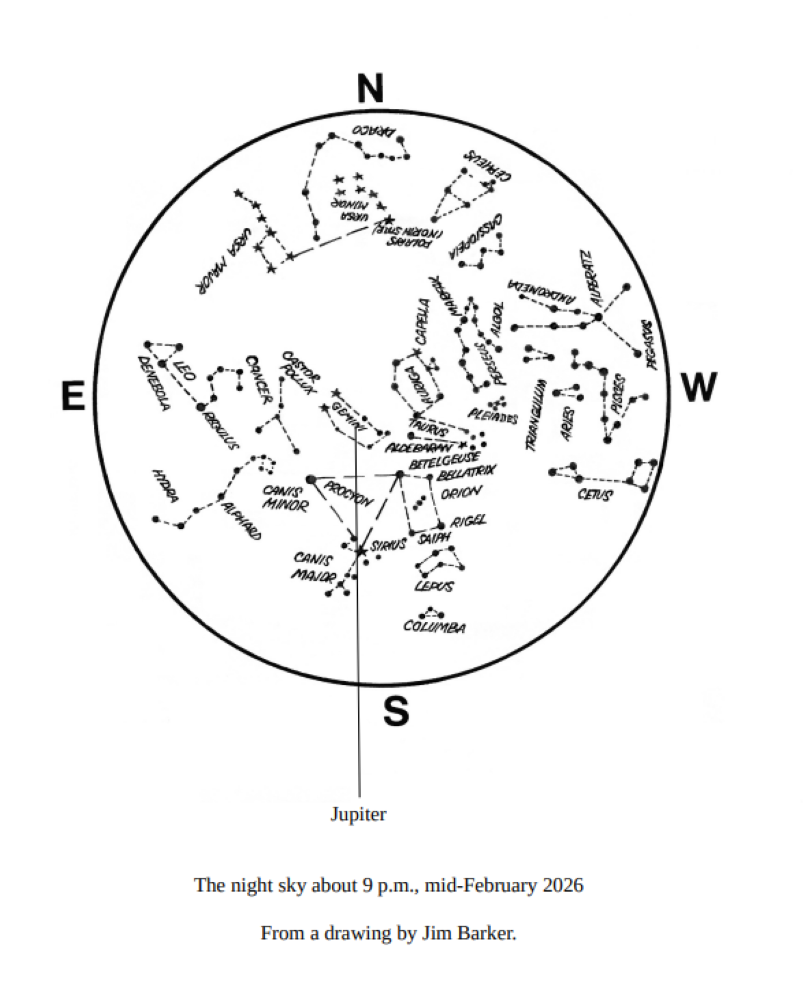

The planet Mercury is in the evening sky, below and right of Saturn after February 8th, above the Moon on the 18th and at greatest elongation from the Sun on the 19th (Fig. 6). Although setting at 7 p.m., it’s at its best for this year, fading and getting lower by the end of the month.

Venus too is now visible by mid-month, after its conjunction with the Sun in January (Fig. 7), and will be below the Moon and Mercury on the 18th and 19th, setting around 7.45 p.m. by the end of February.

On July 5th there’s a possibility that Venus will experience a major meteor shower. 2021 PH27 and 2025 GN1, two asteroids of the Atira group with orbits wholly inside the Earth’s, have orbits so similar that they are probably the results of a break-up between 17,000 and 21,000 years ago, due to solar heating at around 15 million km from the Sun, about four times nearer than Mercury (Keith Cooper, ‘Venus may get a huge meteor shower this July, thanks to a long-ago asteroid breakup’, Space.com, online, 27th January 2026).

Even now they are the fastest asteroids known, circling the Sun in only 115 days. That break-up could have generated a meteor shower like the December Geminids, which come from the asteroid Phaethon, itself a Sun-grazer. Only meteors with magnitudes minus 12 to minus 15, comparable to the Moon’s, would be visible from here, but that raises an interesting thought. There was an occasion when the Salyut 6 cosmonauts reported seeing Venus ‘twinkling like a star’ from above the Earth’s atmosphere (Gordon R. Hooper, ‘Missions to Salyut 6, Part 8’, Spaceflight, Aug/Sept 1979), which is pretty hard to explain – but was Venus in the path of those meteors at the time?

Mars was in solar conjunction at the same time as Venus (Fig. 7), but is moving much more slowly and will not become visible again until June.

More evidence has emerged for a large ocean on Mars in the remote past, occupying the whole of what’s now the northern hemisphere (‘The Boreal Ocean’, Fig. 8).

An international team of researchers, led by the University of Bern in Switzerland, have discovered shorelines and river deltas (Fig. 9) along the edge of Coprates Chasma (Figs. 10 & 11), the deepest part of the huge rift valley of Valles Marineris, discovered by Mariner 10 in 1971 (Fig. 12).

For an idea of scale, Valles Marineris would stretch right across the continental United States, and the smallest of its tributaries would be larger than the Grand Canyon. The Valles was formed by splitting the surface at the formation time of the Tharsis Ridge, where three of Mars’s largest volcanoes stand today, and it’s recently been discovered that a huge outflow of water destroyed a still larger one during those events (see ‘The Sky Above You, April 2024, ON, 7th April 2024). It’s not been clear whether Valles Marineris was joined to the Boreal Ocean or not, but the researchers suggest that the sea level was high enough that it must have been.

Important as their discovery is, it’s not entirely new. The eastern end of Coprates features one of the largest landslides on Mars, and in Candor Chasma to the north, these slice through the lava-filled floors of craters, revealing strangely undisturbed strata below them (Figs. 13 & 14), and the debris radiates so far across the valley floor, up to half way, that at the time of their discovery by Viking Orbiter it was suggested that the Great Rift might have been filled with water at the time – allowing the landslides to billow and spread for vast distances, like the Storegga Slides off the continental shelf of Norway, which wiped out Mesolithic settlement of Scotland with 50-foot high tsunamis in 50-30,000 BC. 1500 feet thick debris spread over 500 miles of deep sea floor, causing tsunamis all round Europe. In 5000 BC Scotland was swept by 70-foot high tsunamis from the same source, (Prof. David Smith, ‘Orkney’s Killer Waves BC’, Orkney Science Festival, Sept. 1991). The comparable Giant Slide into Candor is 30 miles across and extending 120 miles from the wall. That’s not as far as the Storegga Slides, which stretch half-way to Iceland, but the full extent of those wasn’t appreciated at the time of the Viking missions.

Jupiter is still brilliant in Gemini, setting around 5.30 a.m., passed by the Moon on the 26th and 27th. Events with Jupiter’s and Saturn’s moons are described on page 53 of the February issue of Astronomy Now, with full details on page 62.

A recent study suggested that hopes of life in the ocean of Europa (Jupiter’s second large moon, counting outwards) are not realistic because the tidal effects of Jupiter’s pull would not be enough to open geological vents on the sea floor. (Fig. 15; Paul Scott Anderson, ‘Europa’s ocean “quiet and lifeless”, new research suggests’, EarthSky, 15th January 2026). It struck me as premature, when the idea of any tidal activity on the moons of gas giants was held by just one Russian scientist (Vsekhvyatskiy) until the space probe missions of the 1970s, and there are two on the way to study Jupiter’s in much more detail now. But since then there has been the alternative idea that life might evolve and cling to the underside of Europa’s ice cover (see ‘Going Under the Ice‘ and ‘Galileo and the Ice Stars’, ON, 21st September and 28th December, 2025), and that is given a boost by a new paper (Paul Scott Anderson, ‘Life in Europa’s ocean still possible, new research suggests’, EarthSky, January 28th, 2026, citing Washington State University, ‘Study Suggests A Pathway For Life-sustaining Conditions In Europa’s Ocean’, Astrobiology, January 21st, 2026). Drs. Austin Green and Catherine Cooper suggest that organic compounds could be formed in surface ice by radiation from Jupiter, out of ‘salts and other materials’, and then migrate to the ocean by processes known to occur in the Earth’s crust (Fig. 16).

I would immediately want to know what those ‘other materials’ are – sulphur is definitely deposited from the volcanoes on Io, and absorbed into the interior. Perhaps other elements essential for life could come from impacts by comets and carbonaceous asteroids? These two papers may well be precursors for a major debate, as results from Europa Clipper and Jupiter Icy Moons Explorer (JUICE) come in during the 2030s.

Saturn in Pisces sets about 8 p.m., with the Moon nearby on the 19th.

Uranus in Taurus, below the Pleiades (in the same binocular field of view), sets about 1.30 a.m., near the Moon on the 27th.

Neptune in Pisces, only three degrees above Saturn last month, is passed by it, on the left, on the 20th. Neptune also sets around 8 p.m.. with the Moon nearby on February 20th.

Duncan Lunan’s recent books are available from booksellers and through Amazon; details are on Duncan’s website, www.duncanlunan.com.

Click on this link to download a copy of the February Sky Map.

Leave a Reply